Code

# !pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2“Perception is not a collection of fragmented single senses, but a harmonious symphony of all senses.” - James Gibson, founder of ecological psychology.

There has been a long-standing challenge in the history of artificial intelligence. It is “multimodality”. Humans perceive the world by using various senses (modalities) such as vision, hearing, and touch simultaneously, and integrate them organically. For example, when we drink coffee in a cafe, we receive various information such as the warmth of the cup (tactile), the smell of coffee (olfactory), the sound of people talking around us (auditory), and the scenery inside the cafe (visual), and form a comprehensive experience of “being in a cafe”.

However, early artificial intelligence models had difficulty processing this multimodal information. Artificial intelligence research, which began in the 1950s, focused primarily on processing single modalities (text, images, speech). While there were significant achievements in each field, such as translation and speech recognition, integrating them to understand like humans was another dimension of the problem.

In this chapter, we will delve into the core theories and surviving architectures of multimodal deep learning. We will examine how each architecture extends and evolves the DNA of deep learning, and how they contribute to solving complex problems in the real world.

Challenge: How can different forms of data such as text, images, and audio be integrated and processed in a single model? These data have different representation methods, dimensions, and statistical characteristics. How can heterogeneous information be fused to learn meaningful representations?

Researcher’s Concerns: Researchers had to find new methods that could effectively model the interactions between modalities while maintaining their unique characteristics, i.e., a new DNA for deep learning. A true fusion was needed, where each modality understands the context of others and provides complementary information, beyond simple concatenation.

Multimodal data refers to the combination of two or more different forms of data such as text, images, audio, and video. For example, news articles consist of text and images, while movies are composed of video and audio. Humans naturally integrate this multimodal information to understand the world. It is perfectly normal for humans to read words while looking at pictures, listen to sounds while understanding situations.

Why was multimodal deep learning a difficult problem?

Heterogeneous data representation: Text, images, and audio have different representation methods, dimensions, and statistical characteristics. It was a challenging problem to effectively represent and process these heterogeneous data in a single model.

Complexity of information fusion: Simply concatenating each modality’s information does not constitute true fusion. Complex interactions need to be modeled where each modality understands the context of others, provides complementary information, and sometimes reconciles conflicting information.

Data scarcity and imbalance: Multimodal data is relatively scarce compared to single-modality data, and there is also an issue of data imbalance between modalities. For example, there are many datasets that pair images with text, but fewer datasets that include all three: images, text, and audio.

Despite these challenges, deep learning has presented new possibilities for processing multimodal data. Since the 2010s, the advancement of deep learning technology, particularly the emergence of the Transformer architecture, has played a crucial role in the development of multimodal deep learning. This was an important turning point in the evolution of deep learning DNA. The self-attention mechanism of Transformers enabled effective modeling not only of relationships between elements within each modality but also of complex interactions between different modalities. Previously, CNNs were specialized for image processing and RNNs for sequence data, while Transformers provided a universal architecture that could be applied to various modalities with flexibility.

Multimodal deep learning is an essential technology for artificial intelligence to understand the world like humans and interact with it. It goes beyond simply processing multiple forms of data, organically connecting the meanings contained in each data to enable richer and more accurate inferences. Just as different areas of the brain cooperate to perform complex cognitive functions, multimodal deep learning is a core driving force that elevates the intelligence of artificial intelligence.

Main Application Fields

Visual Question Answering (VQA): Takes an image and a question (text) as input and generates an answer to the question. It must comprehensively understand the meaning of the image and the question, beyond simply recognizing objects in the image. For example, to answer the question “What color hat is the man in the picture wearing?”, a complex process of finding the man, recognizing the hat, and determining the color is necessary.

Image Captioning: Automatically generates text that describes an image. It must accurately grasp the content of the image and express it in natural sentences.

Multimodal Sentiment Analysis: Integrates text, voice, facial expressions, and other information to understand a user’s emotions. It can detect subtle changes in emotions or sarcastic tones through voice tone or facial expression changes that might be difficult to discern from text alone.

Autonomous Driving: Integrates data from cameras (images), LiDAR (3D sensors), GPS (location information), radar, and other sensors to recognize the surroundings and make driving decisions. Each sensor provides different information, and fusing them is crucial for safe and accurate driving.

Robotics: Robots integrate visual, tactile, auditory, and other sensory information to perform complex tasks. For instance, for a robot to grasp an object, it must visually identify the object’s location and shape and adjust its grip force based on tactile feedback upon contact.

Medical Diagnosis: Combines X-ray, MRI (images), patient records (text), bio-signals (time-series data), genomic information, and more to diagnose and predict diseases. Each type of data provides different clues about the disease, and integrating them is necessary for accurate diagnosis.

The research on multimodal deep learning is an interesting journey that shows the evolution of deep learning DNA. This journey can be broadly divided into the following major stages:

In the early 2010s, initial research on multimodal deep learning focused primarily on image captioning and VQA (Visual Question Answering). During this period, CNN-RNN based models were prevalent, using CNNs to extract features from images and RNNs to process text. CNNs effectively captured spatial features in images, while RNNs processed sequential information in text with strength. However, early models mainly used the late fusion approach, which processed each modality independently and then combined the results in the final stage. This method had the advantage of preserving the unique characteristics of each modality, but it had the limitation of not fully reflecting the interaction between modalities in the early stages.

Representative models of this period include DeViSE (Frome et al., 2013), which projected images and word embeddings into the same space to calculate image-text similarity, and m-RNN (Mao et al., 2014), which combined CNN and RNN for image captioning and added a multimodal layer to fuse multimodal information.

In the mid-2010s, the introduction of the attention mechanism brought about a significant turning point in multimodal deep learning research. The attention mechanism allowed for more sophisticated modeling of the relationship between images and text. For example, in image captioning, attention enabled the model to learn which region of the image to “focus” on when generating a specific word, and in VQA, it helped determine which part of the image to look at to answer a question.

The introduction of the attention mechanism greatly improved the performance of image captioning and VQA models. Representative models include Show, Attend and Tell (Xu et al., 2015), which introduced attention to image captioning to focus on the relevant image region when generating words, and Stacked Attention Networks (Yang et al., 2016), which applied attention multiple times to the image to generate answers to questions in VQA.

In 2017, the introduction of the Transformer architecture in the paper “Attention is All You Need” marked a new era for multimodal deep learning. The Transformer had the advantage of directly modeling the relationships between all elements in the input sequence using self-attention mechanisms.

Recent multimodal deep learning research is advancing beyond simple information fusion to enhance the ability to generate new knowledge and inference based on the information from each modality.

Advancements in LMM (Large Multimodal Model): More advanced LMMs are emerging, integrating more modalities (such as audio, video, 3D sensor data) and possessing more complex reasoning capabilities.

Research on Efficient Fusion Techniques: On the other hand, research is also being actively conducted on efficient fusion techniques that can maximize the effect of information fusion while reducing computational costs, allowing multimodal models to be effectively utilized even with limited computing resources.

Explainability (XAI) and Ethical Issues: As the complexity of multimodal models increases, the importance of research on understanding the decision-making process of models and addressing ethical issues such as bias is also growing.

In the next section, we will take a closer look at the early approaches to multimodal deep learning and the major architectures that have “survived” the process.

As seen in Section 10.1.3, Transformers and CLIP have brought innovations to multimodal deep learning. However, these advances were not sudden. Prior to this, there were numerous attempts to combine images and text, and further, various modalities, which laid the solid foundation for modern multimodal deep learning. In this section, we will explore the major approaches that led the early days of deep learning-based multimodal research in the early 2010s and their significance.

Image captioning is a task that automatically generates a natural language sentence (caption) describing a given image. This is a representative multimodal problem that converts visual information (image) into linguistic information (text), which was the primary research target in the early days of deep learning-based multimodal research. Image captioning is similar to when a child looks at a picture book and says, “There’s a dog here, and there’s a ball!”

In the early days of image captioning research, models that combined CNNs and RNNs were dominant. It was similar to connecting two hemispheres of the brain: CNN for vision and RNN for language. CNNs were used as image encoders, such as VGGNet and AlexNet, to extract feature vectors from images, while RNNs were used as text decoders, such as LSTMs, to generate caption sentences based on the image feature vectors.

A representative model is Show and Tell (Vinyals et al., 2015), which proposed an end-to-end approach that inputs the image features extracted by CNN into the initial hidden state of LSTM to generate captions. However, this CNN-RNN structure had limitations in that it could not clearly model the correspondence between specific regions of the image and specific words in the text, although it grasped the overall content of the image.

The attention mechanism, which “focuses” on specific regions of the image, greatly improved the performance of image captioning models. Attention is similar to when our gaze naturally moves to important parts of a picture.

There are Soft Attention and Hard Attention mechanisms. Soft Attention calculates weights for all regions of the image and uses a weighted average of feature vectors, while Hard Attention selects only one specific region of the image to generate captions.

Show, Attend and Tell (Xu et al., 2015) was the first model to introduce the Soft Attention mechanism to image captioning, which learned to focus on specific regions of the image when generating each word in the caption, resulting in more accurate and detailed captions.

Since 2017, the Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention approach has emerged, which utilizes both the overall context (top-down) and individual object (bottom-up) information of the image. The bottom-up approach uses object detection models such as Faster R-CNN to identify major objects in the image, while the top-down approach calculates attention weights for these object features during caption generation.

The Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention (Anderson et al., 2018) model combined these two approaches, significantly improving image captioning performance. This is similar to considering the overall flow of a story while detailing the objects in each scene.

Image captioning research added important elements to the DNA of deep learning. The combination of CNN-RNN presented a basic framework for effectively combining different modalities, and attention mechanisms became a key technology in multimodal deep learning. Additionally, Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention further enhanced the image understanding capabilities of deep learning models.

These advancements have become the foundation for extending beyond image captioning to various multimodal tasks such as VQA and multimodal machine translation. Recently, transformer-based models like BLIP have emerged, demonstrating good performance not only in image captioning but also in various multimodal tasks.

BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training) is a transformer-based model for image captioning. BLIP pre-trains images and text together, showing good performance not only in image captioning but also in various multimodal tasks such as VQA and image-text retrieval.

The following is an example code that generates image captions using the BLIP model with the Hugging Face Transformers library.

# !pip install dldna[colab] # in Colab

# !pip install dldna[all] # in your local

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2from transformers import BlipProcessor, BlipForConditionalGeneration

from PIL import Image

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load the model and processor

processor = BlipProcessor.from_pretrained("Salesforce/blip-image-captioning-base")

model = BlipForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained("Salesforce/blip-image-captioning-base")

# Download the image

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000000632.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

# Display the image

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

# Preprocess the input

inputs = processor(image, return_tensors="pt")

# Generate the caption

outputs = model.generate(**inputs)

# Decode and print the caption

caption = processor.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True)

print("Generated caption:", caption)

Generated caption: a bedroom with a bed and a windowVisual Question Answering (VQA) is a task that generates answers to questions about an image based on its content. If image captioning describes the content of an image, VQA is a question-answering process for images. For example, it answers questions like “What is the cat eating?” VQA requires more complex and high-dimensional image understanding capabilities than image captioning, especially the ability to understand and infer the relationship between the image and the question (text).

Like image captioning, early VQA models used a structure that combined CNN and RNN. They extracted image features using CNN, encoded questions using RNN, and then combined these two features to generate answers. However, simply combining image features and question features made it difficult to answer complex questions.

As the attention mechanism was successful in image captioning, it was also introduced to VQA. Co-Attention applies attention to both images and questions, calculating the relevance between each word of the question and each region of the image. This allows for more accurate identification of image regions related to the question.

Stacked Attention repeats attention multiple times to gradually understand the complex relationship between the image and the question. It’s similar to a detective looking at a picture multiple times to deeply understand its relevance to the question.

Representative models include Stacked Attention Networks (SAN) (Yang et al., 2016) and Dual Attention Networks (DAN) (Nam et al., 2017). SAN is a model that applies attention to images multiple times to generate answers to questions, while DAN calculates attention separately for images and questions and combines them to generate answers.

The biggest difference between image captioning and VQA is the integration of external knowledge. To further improve the inference capabilities of VQA models, research has been conducted to utilize external knowledge (common sense, encyclopedia knowledge, etc.). The Knowledge Base (KB) uses structured knowledge bases such as Wikipedia and ConceptNet to provide information needed to find answers to questions.

Memory Networks store external knowledge in memory form and use it to generate answers by searching for relevant information in memory according to the question. However, effectively utilizing external knowledge is still a challenging task. There are many problems to be solved, including the imperfection of the knowledge base, judgment of relevance to questions, and complexity of the inference process.

VQA research has added important genes to deep learning DNA. The combination of CNN-RNN shares a basic framework with image captioning for combining images and text. Multimodal attention gives deep learning models the ability to model complex relationships between images and questions. This means that deep learning models can understand and infer interactions between information, rather than just combining it.

External knowledge integration has opened up the possibility for deep learning models to perform higher-level inferences using external knowledge. This shows that deep learning models can utilize human knowledge and experience, rather than just relying on data. 10.2.1 and 10.2.2 sections reviewed image captioning and VQA, which were two important pillars of early multimodal deep learning research. These studies greatly contributed to applying and advancing the core technologies of deep learning, such as CNN, RNN, and attention mechanisms, to multimodal problems, and became an important foundation for the emergence of more powerful multimodal models based on transformers (CLIP, DALL-E, GPT-4V, Gemini, etc.).

Recently, transformer-based VQA models like ViLT (Vision-and-Language Transformer) have emerged, showing good performance. ViLT inputs image patches and text tokens into the same transformer model, effectively modeling complex interactions between images and text.

ViLT (Vision-and-Language Transformer) is one of the representative transformer-based VQA models. ViLT inputs image patches and text tokens into the same transformer model, effectively modeling complex interactions between images and text.

The following is an example code for performing VQA using the ViLT model with the Hugging Face Transformers library.

from transformers import ViltProcessor, ViltForQuestionAnswering

from PIL import Image

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 모델과 프로세서 로드

processor = ViltProcessor.from_pretrained("dandelin/vilt-b32-finetuned-vqa")

model = ViltForQuestionAnswering.from_pretrained("dandelin/vilt-b32-finetuned-vqa")

# 이미지 다운로드

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

# 이미지 출력

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off') # 축 제거

plt.show()

# 질문 설정

question = "How many cats are in the image?"

print("Question:", question)

# 입력 전처리

encoding = processor(image, question, return_tensors="pt")

# 추론

outputs = model(**encoding)

logits = outputs.logits

idx = logits.argmax(-1).item()

print("Predicted answer:", model.config.id2label[idx])

Question: How many cats are in the image?

Predicted answer: 2Let’s say we have two types of information: images and text. How can we combine these two pieces of information? The simplest way is to concatenate the image vector with the text vector to create a new vector. Connecting information from heterogeneous data sources is called fusion. Efficiently fusing information from two heterogeneous data characteristics is the core of multimodal learning. One reason why it’s difficult to start multimodal deep learning is that it’s a rapidly evolving field, making systematic organization lacking.

In this section, we will explain multimodal fusion in three main categories based on the methods presented in Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) Multimodal Machine Learning lectures. Although this classification is not the standard for current multimodal research, it is very useful for understanding various fusion techniques systematically.

Joint Representations is a method of representing multiple modalities of data in a single common vector space. It’s like drawing text and images together on one canvas.

Instead of processing each modality’s data separately, they are fused into one integrated feature vector. This vector contains the information of each modality, allowing the model to learn deep correlations between modalities. One model can process multiple modalities, and the model structure is relatively simple and efficient because it compresses and represents multiple modalities’ information in one vector. However, each modality’s unique characteristics may be diluted or lost during the fusion process. If a particular modality has much more information than other modalities, an information imbalance problem can occur. Fusing data from different modalities into one meaningful vector is a very difficult problem.

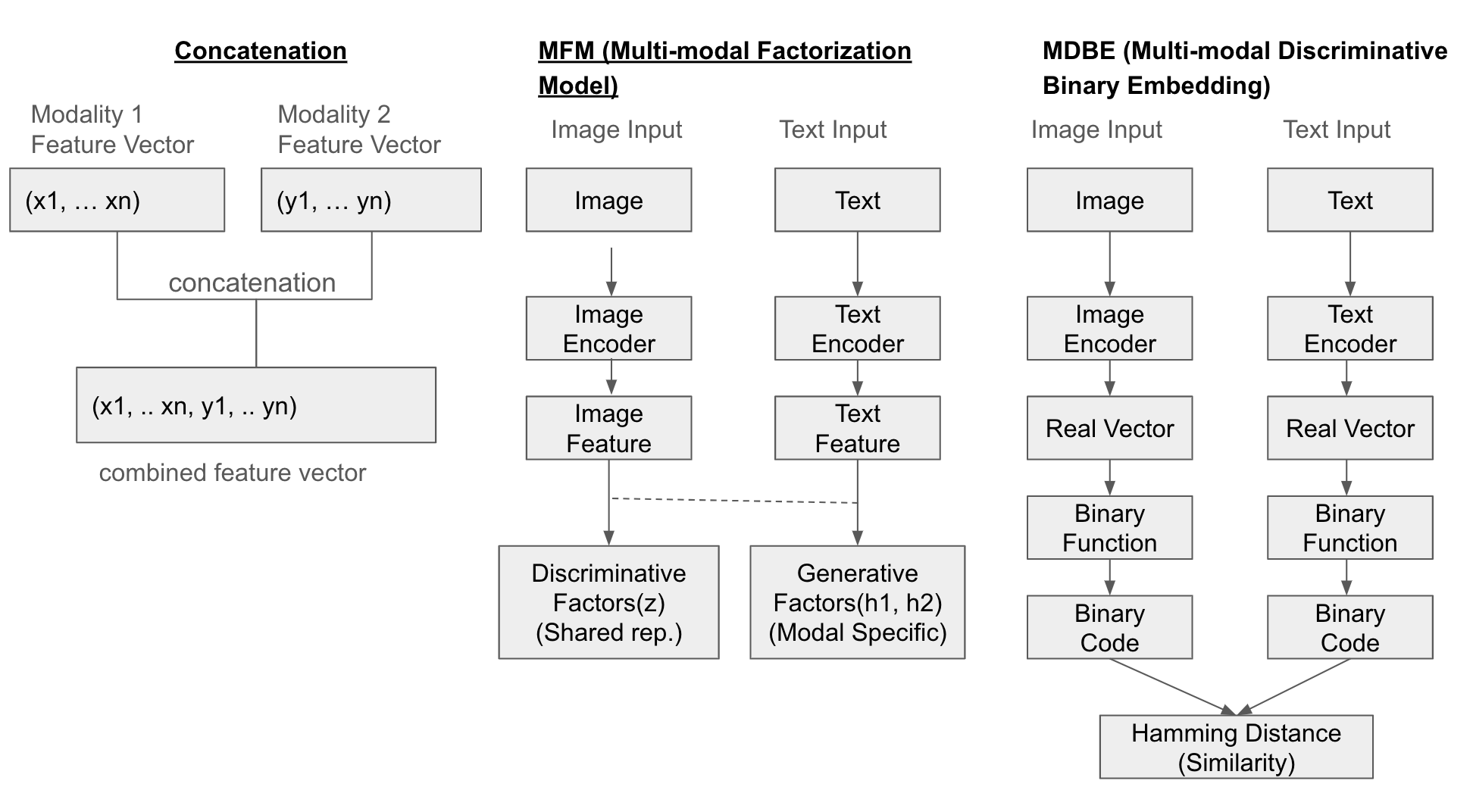

One simple method is to concatenate each modality’s feature vectors. Additionally, the Multi-modal Factorization Model (MFM) combines multiple types of data through matrix factorization to create a common representation space. Multi-modal Discriminative Binary Embedding (MDBE) is a method that represents multimodal data such as images and text as binary codes.

Recent research has proposed methods like COSA (Concatenated Sample), which sequentially connects multiple image-text pairs and applies a transformer-based model to jointly learn visual content and temporal cues. Attentional Concatenation is also used to generate high-resolution images from text, using a multi-level hierarchical structure and utilizing the results of previous layers and word vectors as input for the next layer.

Structural Example

The following diagram illustrates the fusion of three methods (Concatenation, MFM, MDBF).

Example

from transformers import AutoModel, AutoProcessor, AutoTokenizer

from PIL import Image

import torch

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load pre-trained models and processor/tokenizer for image and text

image_model_name = "google/vit-base-patch16-224-in21k" # ViT (Vision Transformer)

text_model_name = "bert-base-uncased" # BERT

image_processor = AutoProcessor.from_pretrained(image_model_name)

image_model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(image_model_name)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(text_model_name)

text_model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(text_model_name)

# Example image and text

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

text = "Two cats sleeping on a couch."

# Display the image

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off') # Remove axes

plt.show()

# Preprocess image and text

image_inputs = image_processor(images=image, return_tensors="pt")

text_inputs = tokenizer(text, return_tensors="pt")

# Feature extraction (embeddings) for each modality

with torch.no_grad(): # Disable gradient calculation (inference mode)

image_features = image_model(**image_inputs).last_hidden_state[:, 0, :] # [CLS] token embedding

text_features = text_model(**text_inputs).last_hidden_state[:, 0, :] # [CLS] token embedding

# Create Joint Representation (Concatenation)

joint_representation = torch.cat((image_features, text_features), dim=1)

print("Image Features Shape:", image_features.shape) # Image feature vector size

print("Text Features Shape:", text_features.shape) # Text feature vector size

print("Joint Representation Shape:", joint_representation.shape) # Combined feature vector size (image + text)Fast image processor class <class 'transformers.models.vit.image_processing_vit_fast.ViTImageProcessorFast'> is available for this model. Using slow image processor class. To use the fast image processor class set `use_fast=True`.

Image Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 768])

Text Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 768])

Joint Representation Shape: torch.Size([1, 1536])Coordinated Representations is a method that represents each modality in a separate space and explicitly learns the relationship between them. It’s similar to having multiple canvas paintings, where each canvas harmonizes with the others.

Each modality is represented as a separate feature vector, but these vectors are learned to “coordinate” with each other. In other words, the feature space of each modality is independent, but their similarities, order relationships, and other meaningful connections are learned to establish a meaningful relationship between them. The advantage of this approach is that it preserves the unique characteristics of each modality while considering its relevance to other modalities. Additionally, it can learn the relationships between various forms of modalities, making it applicable to diverse multi-modal problems.

However, since each modality must be processed separately, the model structure may become more complex than Joint Representations. This can make model design and training more difficult. Furthermore, explicitly learning the relationship between each modality is not an easy task.

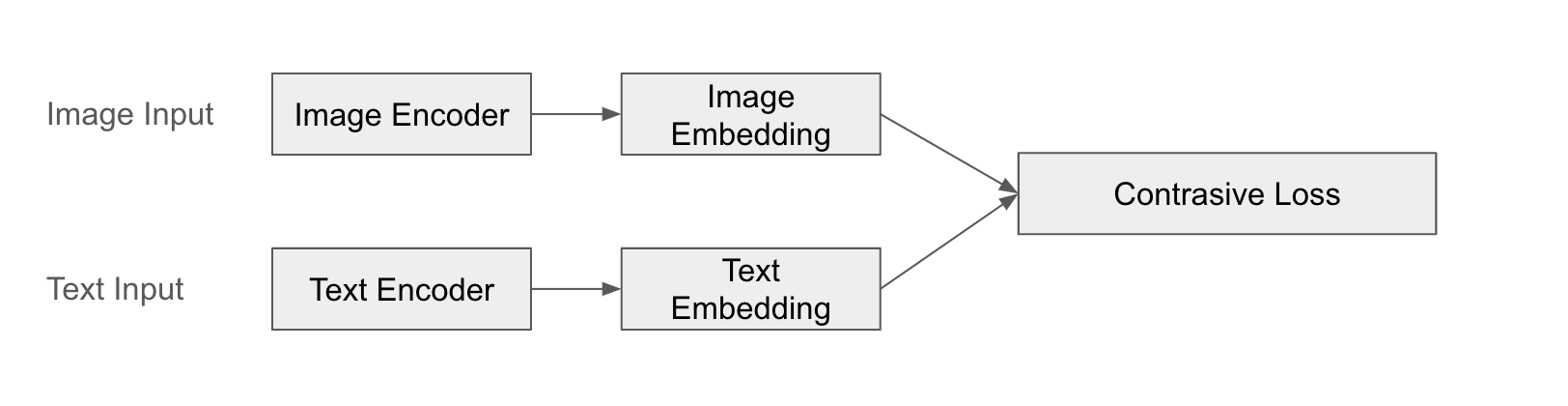

A representative example is CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training). CLIP processes images and text through separate encoders to obtain feature vectors and learns their similarity. CLIP learns to pair images and text, allowing it to understand the meaningful relationship between them.

CLIP’s success is particularly notable in its zero-shot learning ability. A pre-trained CLIP model can classify or search for new images without additional training for a specific task. This is possible because it effectively learns the semantic connection between text and images.

Structure Example

The following is a diagram of CLIP’s fusion.

Example

from transformers import CLIPProcessor, CLIPModel

from PIL import Image

import torch

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load CLIP model and processor

model = CLIPModel.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32")

processor = CLIPProcessor.from_pretrained("openai/clip-vit-base-patch32")

# Example image and text

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

text = "Two cats sleeping on a couch."

# Display image

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off') # Remove axes

plt.show()

# Preprocess image and text

inputs = processor(text=[text], images=image, return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

# Extract image and text features (embeddings)

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

image_features = outputs.image_embeds

text_features = outputs.text_embeds

# Coordinated Representation: Keep features of each modality separate

print("Image Features Shape:", image_features.shape)

print("Text Features Shape:", text_features.shape)

# Calculate similarity between image and text (dot product)

similarity = torch.matmul(image_features, text_features.T) # Or text_features @ image_features.T

print("Image-Text Similarity:", similarity.item())

Image Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 512])

Text Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 512])

Image-Text Similarity: 0.29803216457366943By applying the above method, a simple zero-shot test is possible as follows.

# Zero-shot 이미지 분류

# - 여러 텍스트 후보군을 만들고, 각 텍스트와 이미지 간의 유사도를 계산하여 가장 높은 유사도를 갖는 텍스트를 선택

candidate_texts = ["a photo of a cat", "a photo of a dog", "a photo of a bird"]

inputs = processor(text=candidate_texts, images=image, return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

image_features = outputs.image_embeds

text_features = outputs.text_embeds

logits_per_image = outputs.logits_per_image # 유사도 점수

probs = logits_per_image.softmax(dim=1) # 확률

predicted_class_idx = probs.argmax().item()

predicted_class = candidate_texts[predicted_class_idx]

print("Predicted Class:", predicted_class)

print("Probabilities:", probs)Predicted Class: a photo of a cat

Probabilities: tensor([[9.9403e-01, 5.1377e-03, 8.3070e-04]])The Encoder-Decoder is a method of converting data from one modality to another. It is a technique commonly used in language translation.

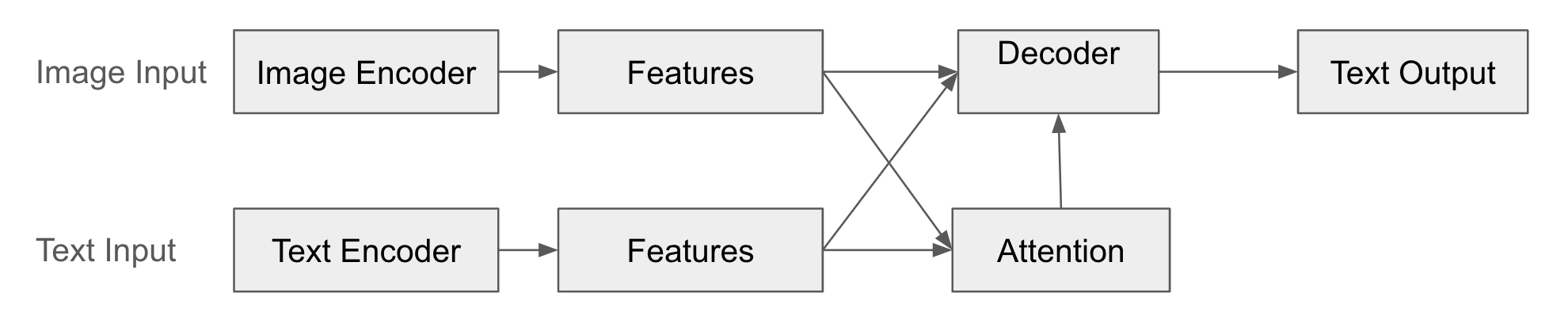

In this structure, the encoder converts the input modality data (e.g., image) into a feature vector. This feature vector compactly represents the core information of the input data. The decoder generates data of another modality (e.g., text) based on the feature vector created by the encoder. The decoder “interprets” the output of the encoder to create new data. Additionally, through the attention mechanism, the decoder learns which part of the encoder’s feature vector to “pay attention” to when generating output data.

The advantage of this method is that it can be applied to various tasks that connect different forms of data, such as image captioning, VQA, and machine translation. It can also be applied even if the input and output modalities are different, and various combinations such as text-image, image-text, and audio-text are possible.

Representative examples include image captioning and VQA (Visual Question Answering). Image captioning processes an image with an encoder to obtain a feature vector and uses a decoder to generate a caption (text). VQA processes an image and a question (text) separately with encoders, uses an attention mechanism to understand the relationship between the image and the question, and then uses a decoder to generate an answer (text).

However, if the input or output data becomes longer, information loss may occur or the amount of computation may increase. In particular, in the case of RNN-based models, it may be difficult to learn long-distance dependencies due to the gradient vanishing problem. Additionally, since the encoder and decoder must be trained simultaneously, training can be unstable or difficult.

Structure Example

The following is a diagram of the Encoder-Decoder fusion.

Example

from transformers import BlipProcessor, BlipForConditionalGeneration

from PIL import Image

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load model and processor

processor = BlipProcessor.from_pretrained("Salesforce/blip-image-captioning-base")

model = BlipForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained("Salesforce/blip-image-captioning-base")

# Download image

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000000139.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

# Display image

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off')

plt.show()

# Input text (optional - Conditional Generation)

# text = "describe this image:" # Prompt (guide image description)

text = "a photo of"

# Preprocess image and text (optional)

# If text is provided, it uses the text as a prompt to generate the caption.

inputs = processor(image, text=text, return_tensors="pt")

# Generate caption

outputs = model.generate(**inputs)

# Decode and print caption

caption = processor.decode(outputs[0], skip_special_tokens=True)

print("Generated caption:", caption)

Generated caption: a photo of a living room with a television and a fireplaceThis example shows image captioning, a representative example of the Encoder-Decoder structure. The encoder takes an image (BLIP’s visual encoder) as input and extracts feature vectors. The decoder generates text (BLIP’s text decoder). It determines which part of the image feature vector to focus on through the attention mechanism while generating captions. You can specify a prompt that affects the caption generated as text. Although BLIP can use both images and text as inputs, here we only use images as inputs and generate text in the decoder.

In sections 10.3.1, 10.3.2, and 10.3.3, we looked at the three core theories of multimodal fusion: Joint Representations, Coordinated Representations, and Encoder-Decoder. Each method has its own characteristics and advantages and disadvantages, so it is important to select the appropriate method according to the application field.

In multimodal deep learning, “fusion” refers to the core process of combining information from different modalities to create a richer and more powerful representation. Although we briefly reviewed CMU lecture-based fusion theory in Section 10.3, actual multimodal fusion research has been much more diverse and dynamic. In this deep dive, we will analyze various classification systems for fusion and the latest research trends in depth, and examine which technologies are being noted as of 2025.

Multimodal fusion is difficult to classify based on a single criterion. Researchers classify fusion methods from various perspectives, and each classification is not mutually exclusive but complementary.

This classification focuses on “which stage” of the multimodal deep learning model the fusion occurs. (Refer to Section 10.3.4)

Early Fusion: Combines “raw” data (or features processed very early) from each modality at the input stage of the model.

Late Fusion: Processes each modality with a separate model and combines the outputs (e.g., prediction results) at the final stage.

Hybrid Fusion: Combines Early Fusion and Late Fusion. It performs fusion at multiple stages of the model to utilize information at various levels.

Model-Agnostic Fusion: General fusion techniques that do not depend on specific models (e.g., Early, Late, Hybrid Fusion).

Model-Specific Fusion: Fusion techniques specialized for specific model structures.

Latest Research: The MULA 2025 workshop, to be held on June 11-12, 2025, will discuss model structures for effectively fusing various sensor data (camera, LiDAR, radar, etc.) in the field of autonomous driving. This workshop aims to encourage interdisciplinary interactions and collaborations between computer vision, multimedia, remote sensing, and robotics communities, with a particular focus on multimodal approaches in autonomous driving.

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Fusion:

Symmetric: Treats all modalities equally.

Asymmetric: Gives more weight to certain modalities or assigns different roles.

Latest Research: “Learning Deep Multimodal Feature Representation with Asymmetric Multi-layer Fusion” proposed an effective framework for fusing multimodal features in multiple layers within a single network. This study introduced two asymmetric fusion operations, channel shuffle and pixel shift, to learn different features according to various fusion directions. Additionally, “Multimodal sentiment analysis based on multi-layer feature fusion,” published in January 2025, presented a new approach for accurate sentiment analysis under modal imbalance and implicit expression conditions.

Explicit vs. Implicit Fusion:

Explicit: Explicitly defines or models the relationships between modalities (e.g., attention mechanisms).

Implicit: Does not directly define the relationships between modalities, but rather allows the model to learn them through training (e.g., simple concatenation).

Latest Research: The HCI International 2025 conference (June 2025) will feature a study comparing the pros and cons of explicit and implicit fusion.

The most notable fusion method in 2024-2025 research is the attention-based mechanism.

Concept: Applies attention to the features of one modality (key-value) using the features of another modality as a query. (Refer to Section 10.4.2) This allows the model to finely capture the relationships between specific elements of different modalities.

Advantages: Can capture fine-grained and flexible relationships between modalities. For example, in image captioning, it can focus on the “running” action of a dog in the image when generating the word “running.”

Latest Research

The “Bi-Att3DDet” study, published in January 2025, introduced a bidirectional attention-based fusion method for 3D object detection in autonomous driving. This study proposed a bidirectional interaction approach to maximize the utilization of complementary information between LiDAR and camera data.

The “LANMSFF” study, published in March 2024 and revised in February 2025, combined a lightweight attention-based network with multi-scale feature fusion for multi-view facial expression recognition. This approach simultaneously generates channel and spatial attention maps to emphasize important features and suppress irrelevant ones.

A recent neuroscience study (2025) investigated the impact of cross-modal congruency on sensory information processing and accumulation. The study showed that congruence between auditory and visual stimuli plays a crucial role in the early stages of sensory processing. #### 2.2 Multi-head Attention

Concept: Uses multiple attention heads to capture relationships between modalities from different perspectives. Each head uses different weight matrices (W_Q, W_K, W_V) to transform the input data and calculate attention, allowing each head to focus on different aspects of the input data (e.g., meaning, grammatical structure, style).

Advantages: Can model various types of relationships simultaneously, enabling the learning of richer and more complex representations. For example, when fusing images and text, some heads can focus on the relationship between objects in the image and words in the text, while others focus on the relationship between the overall atmosphere of the image and the tone of the text.

Recent Research: Recent large-scale multi-modal models (LMMs) have further expanded and refined this technique, effectively modeling complex interactions between various modalities such as images, text, audio, and video.

Contrastive Learning:

Concept: Learns to place related modality pairs (e.g., an image and its caption) close together in the embedding space and unrelated pairs far apart.

Advantages: Can be effectively learned from large-scale unlabeled datasets, helping to alleviate data scarcity issues.

Recent Research: “Dual-Level Cross-Modal Contrastive Clustering” (2024) proposes a new contrastive learning method to bridge the gap between visual representations and text semantics.

Masking-Based Learning:

Concept: Masks parts of the input and learns to recover them using information from other modalities.

Advantages: Can learn complementary relationships between modalities. For example, it can learn to predict masked parts of an image using text descriptions or predict masked words in text using images.

Recent Research: CAST (2025) improved the alignment between graph structure nodes and text tokens through a Masked Node Prediction (MNP) pre-training strategy.

Token-Level Fusion: Models fine-grained interactions between individual tokens of each modality (e.g., image patches, text tokens).

Advantages: Enables more nuanced capture of relationships between modalities. For example, it can learn direct correspondence relationships between specific objects in an image and specific words in text.

Recent Research: CAST (2025) demonstrated that token-level fusion outperforms instance-level fusion in the field of materials science, particularly in graph node and text token fusion.

Instance-Level Fusion: Treats each modality’s entire instance (e.g., an entire image, entire text) as a single unit for fusion.

Advantages: High computational efficiency and simple implementation.

Disadvantages: May fail to capture detailed relationships within modalities.

Multi-modal fusion can be classified in various ways, each providing different perspectives. In actual research, these classifications are often combined and used together. As of 2025, multimodal fusion research focuses on developing efficient fusion techniques using fine-grained interactions at the token level, cross-attention mechanisms, and self-supervised learning methods. In particular, major academic events such as the CVPR 2025 workshop (June 2025, Nashville) will actively discuss advances in multimodal fusion technology in various application fields, including autonomous driving, medical diagnosis, and materials science.

Through this deep dive, we will understand the various classification systems of multimodal fusion and grasp the characteristics of each approach, allowing us to analyze the various multimodal models introduced later more in-depth.

There is no original text provided to translate.

From Sections 10.3.1 to 10.3.3, we examined ways to fuse multimodal data. This is a theoretical classification. When actually designing a multimodal model, it is necessary to strategically decide which fusion method to apply, when, and how, according to the characteristics of the given problem and data. In this section, we will look at sophisticated modality integration strategies adopted by state-of-the-art multimodal models.

Early fusion combines the inputs of multiple modalities in the early stages of the model. The simplest form is to concatenate the feature vectors of each modality. The advantage of early fusion is that it is easy to capture low-level interactions between modalities. For example, if the color of an image and a specific word in text are strongly related, early fusion can easily learn this relationship. However, it may not fully utilize the characteristics of each modality. In particular, when specialized processing is required for each modality (e.g., CNN for images and RNN for text), early fusion can be inefficient.

Recent studies have also presented benchmarks that validate the effectiveness of early fusion in environments with noisy multimodal data, beyond simple concatenation.

Let’s take a look at a simple example of early fusion. This is an example where joint representation uses concatenation for early fusion. The same code is used. Finally, a simple linear classifier is used to determine whether there is a cat or not.

from transformers import AutoModel, AutoProcessor, AutoTokenizer

from PIL import Image

import torch

import requests

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 이미지와 텍스트를 위한 사전 학습된 모델 및 프로세서/토크나이저 로드

image_model_name = "google/vit-base-patch16-224-in21k" # ViT (Vision Transformer)

text_model_name = "bert-base-uncased" # BERT

image_processor = AutoProcessor.from_pretrained(image_model_name)

image_model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(image_model_name)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(text_model_name)

text_model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(text_model_name)

# 예제 이미지 및 텍스트

url = "http://images.cocodataset.org/val2017/000000039769.jpg"

image = Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw)

text = "Two cats sleeping on a couch."

# 이미지 출력

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off') # 축 제거

plt.show()

# 이미지와 텍스트 전처리

image_inputs = image_processor(images=image, return_tensors="pt")

text_inputs = tokenizer(text, return_tensors="pt")

# 각 모달리티에 대한 특징 추출 (임베딩)

with torch.no_grad(): # 기울기 계산 비활성화 (추론 모드)

image_features = image_model(**image_inputs).last_hidden_state[:, 0, :] # [CLS] 토큰 임베딩

text_features = text_model(**text_inputs).last_hidden_state[:, 0, :] # [CLS] 토큰 임베딩

# Joint Representation 생성 (Concatenation)

joint_representation = torch.cat((image_features, text_features), dim=1)

print("Image Features Shape:", image_features.shape) # 이미지 특징 벡터 크기

print("Text Features Shape:", text_features.shape) # 텍스트 특징 벡터 크기

print("Joint Representation Shape:", joint_representation.shape) # 결합된 특징 벡터 크기 (image + text)

# Joint Representation을 활용한 추가 작업 (예: 분류)

num_labels = 2 # 예: "고양이 없음(0)" "고양이 있음(1)", 두 가지 클래스로 분류

classifier = torch.nn.Linear(joint_representation.size(1), num_labels) # 간단한 선형 분류기

outputs = classifier(joint_representation)

print("Classification Outputs:", outputs)Fast image processor class <class 'transformers.models.vit.image_processing_vit_fast.ViTImageProcessorFast'> is available for this model. Using slow image processor class. To use the fast image processor class set `use_fast=True`.

Image Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 768])

Text Features Shape: torch.Size([1, 768])

Joint Representation Shape: torch.Size([1, 1536])

Classification Outputs: tensor([[0.1817, 0.0355]], grad_fn=<AddmmBackward0>)In the above example, the image and text are directly combined as the output of separate models, ViT and BERT. No additional processing (attention, complex transformation, etc.) is performed on these two vectors before combining the image features and text features. Therefore, this corresponds to early fusion.

Late fusion processes each modality with a separate model and combines the outputs of each model (e.g., prediction results) in the final stage. The advantage of this approach is that it can use models specialized for each modality. For example, pre-trained CNN can be used for images and pre-trained Transformer can be used for text to effectively extract complex features from each modality. However, it only considers high-level interactions between modalities and has a disadvantage that information exchange in the middle stage is difficult.

Late fusion is similar to ensemble techniques, and there are active studies on combining the outputs of models for different modalities to improve performance.

Hybrid fusion combines early fusion and late fusion. It performs fusion at multiple stages of the model to utilize various levels of information. The advantage of this approach is that it can take advantage of both early fusion and late fusion. In other words, it can consider both low-level and high-level interactions between modalities. However, the model structure becomes complex, and there are many hyperparameters to tune.

A representative example of hybrid fusion is Cross-Modal Attention. This method uses the features of one modality as a query to apply attention to the features (key-value) of another modality. This is a representative method for performing fusion in the middle stage.

Recently, in addition to attention, various methods such as gated mechanisms and bilinear pooling have been attempted for mid-level fusion.

Since 2023, large-scale multi-modal models (LMMs) such as Gemini and GPT-4V have introduced more refined modality integration strategies to greatly improve performance.

Selective Fusion Mechanism dynamically determines the importance of each modality and selectively integrates information. For example, when text is included in an image, it strongly associates the visual features of the text area with the text content. This is similar to how humans adjust the importance of visual and textual information according to the situation.

Dynamic Weighting automatically adjusts the contribution of each modality based on the characteristics of the task and input. For example, in visual question answering (VQA) tasks, it assigns different weights to image and text information depending on the nature of the question. For a question like “What is the color of the image?”, it gives more weight to visual information, while for a question like “What does the image mean?”, it gives more weight to textual information.

Task-Specific Fusion optimizes the modality integration method according to the requirements of a specific task. In image captioning, it focuses on one-way transfer from visual to text information, while in visual question answering, it enhances two-way interaction.

These refined integration strategies have greatly improved the performance of multi-modal models. In particular, by dynamically adjusting the role and importance of each modality and optimizing the fusion method according to the task characteristics, they have shown excellent results in tasks that require complex inference, beyond simple information combination. These integrated strategies require large datasets and computational resources, so it is difficult to implement and experiment directly through learning examples. Instead, it is desirable to understand conceptually through the papers and technical documents of each model.

In Section 10.3, we examined various theoretical methods and strategies for fusing multimodal data. Based on this, let’s take a look at the specific techniques that actual multimodal models use to effectively represent information from each modality and learn relationships between different modalities. The entire implementation is in chapter_10/multimodal_embeding.py.

One of the core tasks in multimodal learning is how to represent modalities with different characteristics in a meaningful common space. Images are 2D arrays of pixel values, text is a 1D sequence of tokens, and audio is amplitude values over time, each with its own unique representation method. To effectively process these heterogeneous data, a representation learning technique is needed that captures the essential characteristics of each modality while maintaining the semantic relationships between them.

Early Approach: Individual Encoders + Projection

Early multimodal models used specialized encoders for each modality (e.g., CNN for images, RNN for text) to extract feature vectors, which were then projected into a common vector space using linear transformation or shallow MLP. (Refer to Joint Representation and Concatenation methods in Section 10.3.1)

Recent Approach: Semantic Alignment

Recently, the main approach is to learn semantic alignment between modality-specific feature vectors, rather than simply matching dimensions. In other words, related images and text are learned to be close in the embedding space, while unrelated images and text are learned to be far apart.

Contrastive Learning: (Refer to Coordinated Representation and CLIP example in Section 10.3.2) Image-text pairs are considered “positive” samples, and randomly mixed image-text pairs are considered “negative” samples. The model learns to increase the similarity between positive samples and decrease the similarity between negative samples.

Triplet Loss: Using an image anchor, a positive text (the caption of the anchor image), and a negative text (the caption of another image), the model learns to make the distance between the anchor image and the positive text close, and the distance between the anchor image and the negative text far.

Implementation Example (Contrastive Learning)

class MultimodalEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, embedding_dim=512):

super().__init__()

self.image_encoder = models.resnet18(pretrained=True)

self.image_encoder.fc = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(512, embedding_dim),

nn.LayerNorm(embedding_dim)

)

self.text_encoder = BertModel.from_pretrained('bert-base-uncased')

self.text_projection = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(768, embedding_dim), # BERT output dimension is 768

nn.LayerNorm(embedding_dim)

)

self.logit_scale = nn.Parameter(torch.ones([]) * np.log(1 / 0.07))

def encode_image(self, image):

return self.image_encoder(image)

def encode_text(self, input_ids, attention_mask):

text_features = self.text_encoder(input_ids, attention_mask)[0][:, 0, :] # [CLS] token, keep batch dim

return self.text_projection(text_features)MultimodalEmbedding class:

image_encoder: Uses ResNet18 to convert an image into a feature vector of size embedding_dim.text_encoder: Employs the BERT model to convert text into a feature vector and aligns it to the size of embedding_dim through the text_projection layer.logit_scale: A learnable temperature parameter used in CLIP.Semantic Alignment Mechanism

The semantic alignment is largely implemented in two parts: the forward method of the MultimodalEmbedding class and the constrasive_loss().

def forward(self, image, input_ids, attention_mask):

image_features = self.encode_image(image)

text_features = self.encode_text(input_ids, attention_mask)

image_features = image_features / image_features.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

text_features = text_features / text_features.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

logit_scale = self.logit_scale.exp()

logits = logit_scale * image_features @ text_features.transpose(-1, -2)

# print("logits:", logits.shape)

return logits # Return a single valueforward method:

Uses encode_image and encode_text to encode the image and text, respectively.

Feature Normalization: Applies L2 normalization to set the magnitude of image_features and text_features vectors to 1. This is done to consider only the direction of the vectors when calculating similarity.

Temperature Scaling: Utilizes logit_scale to adjust the distribution of similarity scores. The logit scale is applied to an exponential function to obtain a scaling value, which is then multiplied with the matrix product of the image feature matrix and the transposed text feature matrix. The matrix product calculates the dot product between each image feature vector and all text feature vectors to generate similarity scores.

logits: Calculates the similarity (dot product) between image feature vectors and text feature vectors. Instead of using text_features.t(), text_features.transpose(-1, -2) is used for transposition. This swaps the last two dimensions of the text feature matrix from (batch, text feature dimension) to (batch, feature dimension, text), allowing multiplication with the image feature matrix of shape (batch, image feature dimension).

def contrastive_loss(logits): # removed enhanced_similarity

labels = torch.arange(logits.size(0), device=logits.device) # Use logits.size(0)

# Image-to-text and text-to-image contrastive loss

img_txt_loss = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()(logits, labels)

txt_img_loss = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()(logits.T, labels)

# Average loss

return (img_txt_loss + txt_img_loss) / 2In the contrastive_loss function, labels are generated as integers from 0 to (batch size - 1) to match the size of the logits matrix. The diagonal elements (i, i) in the logits matrix represent the similarity between the i-th image and the i-th text, which is the similarity of the positive pair (image-text pair), so the labels are set to make these diagonal elements correct. Additionally, img_txt_loss calculates the loss of image-to-text similarity, and txt_img_loss calculates the loss of text-to-image similarity. By averaging these two losses, both image-to-text and text-to-image semantic alignments are considered.

The semantic alignment mechanism maps features from different modalities to a semantically consistent space. First, all feature vectors are projected onto a unit sphere using L2 normalization to remove scale differences between modalities. A temperature scaling parameter is introduced to adjust the distribution of similarity values. High temperatures produce softer distributions, while low temperatures produce sharper distributions, increasing learning stability. Additionally, through contrastive learning, related image-text pairs are learned to be close in the embedding space, and unrelated pairs are learned to be far apart. In particular, both image-to-text and text-to-image mappings are simultaneously optimized to achieve bidirectional semantic alignment.

Like CLIP’s contrastive learning, related content is learned to be close, and unrelated content is learned to be far apart. This contrastive learning-based semantic alignment strategy has evolved from OpenAI’s CLIP in 2021 to Google’s PaLM-E, Anthropic’s Claude, and DeepMind’s Gemini. While early CLIP focused on simple contrastive learning of image-text pairs, newer models capture more nuanced relationships between multiple modalities. In particular, Gemini learns semantic alignments between various modalities such as images, text, audio, and video simultaneously, preserving the unique characteristics of each modality while building an integrated semantic space.

Example Execution

The data used for training is Flicker8k. The EnhancedMultimodalEmbedding (or EnhancedMultimodalEmbedding_no_p) model can be trained on the Flickr8k dataset using the train_multimodal_embedding function. In the main function, the model, data loader, optimizer, etc. are set up, and calling the train_multimodal_embedding function starts the training.

# download flickr8k.

!mkdir data;cd data;wget "https://github.com/awsaf49/flickr-dataset/releases/download/v1.0/flickr8k.zip";unzip -q flickr8k.zip -d ./flickr8kmkdir: cannot create directory ‘data’: File exists

--2025-03-09 16:33:12-- https://github.com/awsaf49/flickr-dataset/releases/download/v1.0/flickr8k.zip

Resolving github.com (github.com)... 20.200.245.247

Connecting to github.com (github.com)|20.200.245.247|:443... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 302 Found

Location: https://objects.githubusercontent.com/github-production-release-asset-2e65be/753516996/d7c62b13-1e50-40ea-8fae-f34a44b1695f?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=releaseassetproduction%2F20250309%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20250309T073156Z&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Signature=ff62cf7df8ac3deba8bd6f4f775e164abf03c6d2d6d86d740e5407e52702c6a3&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&response-content-disposition=attachment%3B%20filename%3Dflickr8k.zip&response-content-type=application%2Foctet-stream [following]

--2025-03-09 16:33:12-- https://objects.githubusercontent.com/github-production-release-asset-2e65be/753516996/d7c62b13-1e50-40ea-8fae-f34a44b1695f?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=releaseassetproduction%2F20250309%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20250309T073156Z&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-Signature=ff62cf7df8ac3deba8bd6f4f775e164abf03c6d2d6d86d740e5407e52702c6a3&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&response-content-disposition=attachment%3B%20filename%3Dflickr8k.zip&response-content-type=application%2Foctet-stream

Resolving objects.githubusercontent.com (objects.githubusercontent.com)... 185.199.109.133, 185.199.111.133, 185.199.110.133, ...

Connecting to objects.githubusercontent.com (objects.githubusercontent.com)|185.199.109.133|:443... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 1112971163 (1.0G) [application/octet-stream]

Saving to: ‘flickr8k.zip’

flickr8k.zip 100%[===================>] 1.04G 56.8MB/s in 19s

2025-03-09 16:33:32 (56.9 MB/s) - ‘flickr8k.zip’ saved [1112971163/1112971163]

import torch

from torchvision import models, transforms

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

# Assuming dldna.chapter_10.multimodal_embedding is in the same directory or Python path.

# Adjust if necessary (e.g., from multimodal_embedding import ...).

from dldna.chapter_10.multimodal_embedding import Flickr8kDataset, MultimodalEmbedding, train_multimodal_embedding, generate_example

# Data transformation setup

transform = transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize((224, 224)),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize(mean=[0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std=[0.229, 0.224, 0.225])

])

# Dataset and DataLoader setup

image_dir = './data/flickr8k/Images' # Replace with the actual path to your image directory

caption_file = './data/flickr8k/captions.txt' # Replace with the actual path to your caption file

dataset = Flickr8kDataset(image_dir, caption_file, transform=transform)

train_size = int(0.8 * len(dataset))

val_size = len(dataset) - train_size

train_dataset, val_dataset = torch.utils.data.random_split(dataset, [train_size, val_size])

train_loader = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True, num_workers=4)

val_loader = DataLoader(val_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=False, num_workers=4)

# Model initialization

model = MultimodalEmbedding()

# Model training

train_multimodal_embedding(model, train_loader, val_loader, num_epochs=3)

# Model saving

torch.save(model.state_dict(), 'multimodal_embedding_model.pth')

# Example generation

model_path = 'multimodal_embedding_model.pth'

generate_example(model_path, image_dir, caption_file)Epoch 1/3: 15%|█▍ | 147/1012 [00:16<01:36, 8.96it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 1/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:53<00:00, 8.90it/s]Epoch 1/3 - Train Loss: 0.9618Epoch 1/3 - Validation Loss: 0.5212

Epoch 1: Saved best model with Validation Loss = 0.5212Epoch 2/3: 52%|█████▏ | 525/1012 [00:59<00:55, 8.84it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 2/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:54<00:00, 8.83it/s]Epoch 2/3 - Train Loss: 0.3393Epoch 2/3 - Validation Loss: 0.4240

Epoch 2: Saved best model with Validation Loss = 0.4240Epoch 3/3: 34%|███▍ | 347/1012 [00:39<01:15, 8.85it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 3/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:54<00:00, 8.83it/s]Epoch 3/3 - Train Loss: 0.2313Epoch 3/3 - Validation Loss: 0.3891

Epoch 3: Saved best model with Validation Loss = 0.3891

Image 0:

Top 3 Captions (Image -> Text):

- football players in red congratulate each other as crowds in red cheer behind. (prob: 0.9970)

- a man in black holds up an obama 08 sign. (prob: 0.0023)

- a large group of bicycles racing on the street (prob: 0.0004)

Caption: football players in red congratulate each other as crowds in red cheer behind.

Top 3 Images (Text -> Image):

- Image 0 (prob: 0.9983)

- Image 17 (prob: 0.0013)

- Image 2 (prob: 0.0001)

Cross-modal attention is used to effectively model the relationship between different modalities. This extends ViT’s self-attention to enable interaction between heterogeneous data such as images and text.

Modal Attention Design

Cross-modal attention has an asymmetric structure considering the characteristics of each modality.

class CrossModalAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.image_proj = nn.Linear(config.image_dim, config.hidden_dim)

self.text_proj = nn.Linear(config.text_dim, config.hidden_dim)

self.attention = nn.MultiheadAttention(config.hidden_dim, config.num_heads)

def forward(self, image_features, text_features):

image_proj = self.image_proj(image_features)

text_proj = self.text_proj(text_features)

attn_output, _ = self.attention(text_proj, image_proj, image_proj)

return attn_outputAfter projecting image and text features into a common latent space, the relationship between the two modalities is learned through a multi-head attention mechanism. The text feature is used as a query, and the image feature is used as a key and value, allowing the text to pay attention to the relevant part of the image.

Asymmetric Attention Pattern

An asymmetric attention pattern is used to preserve the unique characteristics of each modality while facilitating effective information exchange.

class HierarchicalCrossModalAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.local_image_attention = nn.MultiheadAttention(config.hidden_dim, config.num_heads)

self.local_text_attention = nn.MultiheadAttention(config.hidden_dim, config.num_heads)

self.image_to_text_attention = CrossModalAttention(config)

self.text_to_image_attention = CrossModalAttention(config)

self.output_layer = nn.Linear(config.hidden_dim * 2, config.hidden_dim)

def forward(self, image_features, text_features):

local_image = self.local_image_attention(image_features, image_features, image_features)[0]

local_text = self.local_text_attention(text_features, text_features, text_features)[0]

image_attended_text = self.image_to_text_attention(image_features, local_text)

text_attended_image = self.text_to_image_attention(text_features, local_image)

combined_features = torch.cat([image_attended_text, text_attended_image], dim=-1)

output = self.output_layer(combined_features)

return outputHere, bidirectional attention is performed separately from images to text and from text to images. This allows each modality to selectively focus on relevant information from the other modality.

Hierarchical Attention Structure

To capture complex multimodal relationships, multiple layers of attention are hierarchically constructed. In the lower layers, local features within each modality are processed, and in the upper layers, global relationships between modalities are modeled. This hierarchical structure plays a key role in models such as GPT-4V and Gemini.

class EnhancedMultimodalEmbedding_no_p(MultimodalEmbedding):

def forward(self, image, input_ids, attention_mask):

image_features = self.encode_image(image)

text_features = self.encode_text(input_ids, attention_mask)

image_features = self.image_preserve(image_features)

text_features = self.text_preserve(text_features)

combined_features = self.cross_modal_attention(image_features, text_features)

combined_features = combined_features / combined_features.norm(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

logit_scale = self.logit_scale.exp()

logits = logit_scale * combined_features @ combined_features.t()

return logitsimport torch

from torchvision import models, transforms

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

from collections import namedtuple

from dldna.chapter_10.crossmodal_attention import Flickr8kDataset, CrossModalEmbedding, train_crossmodal_embedding, generate_example

# Configuration

config = namedtuple('Config', ['embedding_dim', 'image_dim', 'text_dim', 'hidden_dim', 'num_heads'])(

embedding_dim=512, # Output embedding dimension

image_dim=512, # ResNet18 image encoder output dimension

text_dim=512, # Text feature (768 from BERT -> 512 after projection)

hidden_dim=512, # Cross-modal attention internal hidden dimension

num_heads=8 # Number of multi-head attention heads

)

# Data transformation setup

transform = transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize((224, 224)),

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize(mean=[0.485, 0.456, 0.406], std=[0.229, 0.224, 0.225])

])

# Dataset and DataLoader setup

image_dir = './data/flickr8k/Images' # Change to the actual path

caption_file = './data/flickr8k/captions.txt' # Change to the actual path

dataset = Flickr8kDataset(image_dir, caption_file, transform=transform)

train_size = int(0.8 * len(dataset))

val_size = len(dataset) - train_size

train_dataset, val_dataset = torch.utils.data.random_split(dataset, [train_size, val_size])

train_loader = DataLoader(train_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=True, num_workers=4, pin_memory=True)

val_loader = DataLoader(val_dataset, batch_size=32, shuffle=False, num_workers=4, pin_memory=True)

# Model initialization

model = CrossModalEmbedding(config)

# Model training

train_crossmodal_embedding(model, train_loader, val_loader, num_epochs=3)

# Model saving

torch.save(model.state_dict(), 'crossmodal_embedding_model.pth')Epoch 1/3: 4%|▍ | 40/1012 [00:04<01:41, 9.53it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 1/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:47<00:00, 9.41it/s]Epoch 1/3 - Train Loss: 0.9663Epoch 1/3 - Validation Loss: 0.5378Epoch 2/3: 58%|█████▊ | 582/1012 [01:02<00:45, 9.36it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 2/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:48<00:00, 9.31it/s]Epoch 2/3 - Train Loss: 0.3381Epoch 2/3 - Validation Loss: 0.4452Epoch 3/3: 0%| | 4/1012 [00:00<02:27, 6.82it/s]Image file not found: ./data/flickr8k/Images/imageEpoch 3/3: 100%|██████████| 1012/1012 [01:48<00:00, 9.35it/s]Epoch 3/3 - Train Loss: 0.2288Epoch 3/3 - Validation Loss: 0.3743# Example generation

model_path = 'crossmodal_embedding_model.pth'

generate_example(model_path, image_dir, caption_file)Image 0:

Top 3 Captions (Image -> Text):

- two people walk out onto the desert sand. (prob: 0.9862)

- a man takes a picture of him and his friend with his phone. (prob: 0.0092)

- the little boy wearing the blue shirt is putting dirt in his mouth. (prob: 0.0013)

Caption: two people walk out onto the desert sand.

Top 3 Images (Text -> Image):

- Image 0 (prob: 0.9898)

- Image 2 (prob: 0.0089)

- Image 4 (prob: 0.0005)

Perceiver is a multimodal architecture proposed by DeepMind in 2021. It addresses the quadratic complexity issue of existing transformers (where computation increases with the square of the input sequence length) while effectively handling various modalities (such as images, text, audio, and point clouds). The Perceiver is particularly advantageous when the input data size is very large (e.g., high-resolution images, long texts). Here, we describe the overall architecture and omit examples. The code is example code for explanation purposes.

Core Idea of Perceiver

Perceiver is based on the following ideas:

Perceiver uses a fixed-size latent array regardless of the input sequence length. This latent array compresses and represents the information of the input data, summarizing a large amount of input information into a small number of latent vectors, like a bottleneck. Therefore, even if the input data size is very large (e.g., 10,000 tokens), the number of latent vectors is fixed (e.g., 256), which can greatly reduce computational complexity and memory usage.

class Perceiver(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, ..., num_latents=256, latent_dim=512, ...):

super().__init__()

# Latent vector initialization (key!)

self.latents = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(num_latents, latent_dim))

# ...In the above code, self.latents represents that latent vector. It is defined as nn.Parameter, which means it is a learnable parameter.

The Perceiver does not use modality-specific processing methods (e.g., CNN, RNN) for input modalities such as images, text, and audio. Instead, each modality undergoes simple preprocessing (e.g., image patches, text tokenization) to be converted into a common format (sequence of vectors). Subsequent processing uses the same transformer-based architecture (Cross-Attention, Self-Attention) regardless of the modality type. This allows for flexible handling of various modalities and easy addition of new modalities.

The Perceiver uses multiple layers of self-attention to gradually update the latent vectors. At each layer, the latent vectors exchange information with each other and learn complex patterns from the input data. Initially, the latent vectors that represented simple features come to express abstract and high-level meanings as they pass through multiple layers.

How Perceiver Works (Simplified Code Example)

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class Perceiver(nn.Module):

def __init__(self,

input_channels=3, # Input channels (e.g., RGB image)

input_axis=2, # Input dimension (image=2, video=3)

num_latents=256, # Number of latent vectors

latent_dim=512, # Latent vector dimension

num_heads=8, # Number of attention heads

depth=6): # Model depth (number of self-attention layers)

super().__init__()

# 1. Latent vector initialization (key!)

self.latents = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(num_latents, latent_dim))

# 2. Input projection (matches input dimension to latent dimension)

self.input_proj = nn.Linear(input_dim, latent_dim)

# 3. Cross-Attention (learns relationships between input and latent vectors)

# self.cross_attention = nn.MultiheadAttention(latent_dim, num_heads, batch_first=True)

# 4. Self-Attention (learns relationships between latent vectors) - repeated multiple times

self.self_attention_layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.MultiheadAttention(latent_dim, num_heads, batch_first=True)

for _ in range(depth)

])

def forward(self, x): # x: Input data (image, text, ...)

batch_size = x.shape[0]

# 1. Input projection

x = self.input_proj(x)

# 2. Latent vector replication (for each item in the batch)

latents = self.latents.unsqueeze(0).expand(batch_size, -1, -1) # (B, num_latents, latent_dim)

# 3. (Optional) Cross-attention (between input and latent vectors)

# latents, _ = self.cross_attention(latents, x, x) # query, key, value

# 4. Self-attention (between latent vectors) - repeated multiple times

for layer in self.self_attention_layers:

latents, _ = layer(latents, latents, latents) # query, key, value

return latents # Return the processed latent vectorsAdvantages and Disadvantages of Perceiver

Perceiver has the efficiency of having a computational complexity that is almost constant regardless of the input size, and provides flexibility to process various modalities in the same way. Additionally, the expandability of Perceiver, which can easily add new modalities, is also an advantage. However, since Perceiver is still based on a transformer, it has the disadvantage of having a complex structure, and the model can become very large as the dimension of the latent vector and the number of layers increase. Additionally, in specific tasks such as image classification, its performance may be inferior to models specialized for those tasks, such as CNNs.

Perceiver IO

Perceiver IO, a follow-up study to Perceiver, proposed a method to process not only inputs but also outputs through latent vectors. This allows for flexible handling of various output forms (classification, regression, sequence generation, etc.). Perceiver IO is evaluated as a more general and powerful model than Perceiver.

Here, we start with the basic structure of cross-attention and gradually add mechanisms to compare trainability and performance. Through this process, we aim to understand the issues that arise in multimodal learning and explore practical approaches to address them.

When designing cross-attention mechanisms, it is a common and recommended approach to gradually increase complexity as described in this section and experiment with it. This method, known as an ablation study, effectively identifies the importance of each component mechanism and the key elements contributing to the final model’s performance. Many papers proposing new architectures use this approach. Moreover, discussing not only the final performance but also stability issues during training is crucial from a practical perspective.

Comparative Training Methods

Experiments are conducted using the flickr8k dataset, which was previously explored, with text and image as two inputs to train mutual similarity. The training involves versions of cross-attention with increasing complexity. For each version, a cross-attention mechanism is added one by one, and training is performed for comparison. All trainings use the same hyperparameters. The training epoch is fixed at 5.

Structure of Examples

Examples are composed of the following structure:

chapter_10/mm

├── cat_resized.png

├── cross_attention

│ ├── v0.py

│ ├── v1.py

│ ├── v2.py

│ ├── v3.py

│ .... (continue to exist)

├── train_multimodal.py

└── evaluate_models.py

The cross_attention folder increases the complexity of cross-attention sequentially from v1 to v11. train_mulimodal.py dynamically generates and trains the next version of the model after one training is completed. During training, metrics such as accuracy, contrast loss, and execution time are stored to generate a final comparison table. It is not desirable to determine trainability based on loss values and accuracy. The easiest way to check if the training has been done correctly due to the nature of contrastive learning is to evaluate it with data that did not exist before. The file that evaluates the model in a zero-shot manner is evalute_models.py.

The image being evaluated is as follows.

The evaluation is done by measuring the similarity between the above image and five texts.

test_captions = [

"A dog playing in the park",

"A cat sleeping on a couch",

"Children playing soccer",

"A sunset over the ocean",

"A person cooking in the kitchen"

]If the model training is done correctly, the second caption “A cat sleeping on a couch” should have the highest similarity among the five captions. The above image is something that was not in the training data, which corresponds to a typical zero-shot test.

Cross-attention dynamic allocation

Changing the version of cross_attention is done through dynamic allocation.

from dldna.chapter_10.mm.cross_attention.v0 import CrossAttention as v0

from dldna.chapter_10.mm.cross_attention.v1 import CrossAttention as v1

# ... (import other versions) ...

from dldna.chapter_10.mm.cross_attention.v11 import CrossAttention as v11

def get_cross_attention(version, config=None):

if config is None:

config = {}

if version == 'v0':

return v0(**config)